Raspberry Pi Airplay Tutorial

A tutorial that guides you through setting up a Raspberry Pi AirPlay receiver. It then shows you how to use a Raspberry Pi as a web server. By .

Sign up/Sign in

With a free Kodeco account you can download source code, track your progress, bookmark, personalise your learner profile and more!

Create accountAlready a member of Kodeco? Sign in

Sign up/Sign in

With a free Kodeco account you can download source code, track your progress, bookmark, personalise your learner profile and more!

Create accountAlready a member of Kodeco? Sign in

Contents

Raspberry Pi Airplay Tutorial

40 mins

- Getting Started: What You’ll Need

- A Brief Introduction to the Raspberry Pi

- Loading the Operating System

- Downloading the Image

- Loading the Image onto the Card

- SSHing into Raspberry Pi

- Expanding the File System

- Setting Up the Project

- Updating the Packages

- Changing the Default Audio Port

- Installing the Prerequisites

- Installing Perl Net-SDP

- Setting up your Raspberry Pi AirPlay receiver

- Installing and Running Shairport

- Live From Your Raspberry Pi…

- Daemonizing Shairport

- Setting Up A Web Server

- Calling in the Apache

- Installing MySQL

- Installing PHP

- Setting Up the Database

- Running the Web Service Script

- Changing Your Password

- Examining the Script

- Testing the Script

- Using the Web Services with an iOS App

- Where to Go from Here?

Make your Raspberry Pi into an AirPlay receiver!

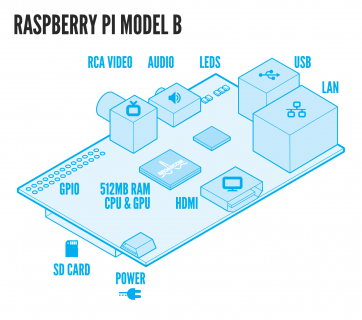

The Raspberry Pi is a full Linux computer that is about the size of a credit card and sells for $25–$35. It has a 700Mhz ARM CPU and 512MB of RAM. Because of its capabilities and its low price, it has become wildly popular with the hobbyist market. Some people have done ingenious things with theirs.

If you’re like me, you toyed with the idea of getting an AirPort Express in the past but the $100 price seemed a bit steep, since all you really wanted to do with it is play audio using AirPlay. Sound familiar?

Maybe you also have a new Raspberry Pi and don’t know what to do with it. Well, guess what – you can turn that baby into an AirPlay speaker. That’s right, instead of spending $100 on an AirPort Express, you can put together a cool DIY AirPlay receiver for around $45 using the Raspberry Pi. That’s what you’re going to do in this tutorial. By the end of it you’ll have your very own Raspberry Pi AirPlay receiver!

After that, you’ll look further into the usefulness of the Raspberry Pi to iOS developers. Most complex apps need some sort of backend web service and a Raspberry Pi is a perfect server for development or perhaps even a small app. You’ll install the Apache web server, MySQL database and PHP, then use them to create a web service that you can access from an iOS chat app.

Getting Started: What You’ll Need

Here are the hardware components you’ll need for this project (places to buy the equipment listed next to each component):

- Raspberry Pi. (Buy)

- SD Card. (Amazon) 4 GB is all you should need for this project. This is the storage for the project and will act as the hard drive for the Raspberry Pi.

- Ethernet cable/jack. The Raspberry Pi doesn’t have WiFi built in so we’ll use the wired connection

- OS X or Linux computer on which you have sudo rights. You’ll need a computer to load the OS onto the SD Card and to SSH into the Raspberry Pi.

- Memory card reader. The one built into your computer will work fine if it has one. You need this to load the OS onto the memory card.

- iPhone or iPad. You going to use this to airplay audio from and to run the demo app

- Micro-USB cable. (Buy) To power the Raspberry Pi.

- Set of speakers with a mini audio cable.(This is just to normal analog audio connecter) So you can hear the AirPlayed audio

You’re going to download and run Shairport, a project that emulates the proprietary Apple AirPort protocol with software so that Raspberry Pi will appear as an AirPort receiver on your network. The AirPlay protocol isn’t something that Apple publishes publicly but somebody reverse engineered it and created an executable that will appear as an AirPlay receiver. You can check out the open source project here.

A Brief Introduction to the Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi is quite a little device. Although not the first of its kind, it has exploded in popularity because it has combined very capable, full feature computer hardware in a tiny form factor at a unbelievable price ($25-35). It has a 700Mhz ARM CPU with 512 MB of RAM with all the standard connectors that you would expect to come on a computer like an analog audio out port, 2 USB ports, wired ethernet, and analog RCA and digital HDMI video out for connecting a monitor. In addition to that, it has a bank of GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) pins for connecting to hardware. These can be used for anything from simply controlling a LED to a motor to reading from any number of different kinds of sensors.

There is also a SD Card reader onboard. There is no onboard memory on the Raspberry Pi so all files are kept on a SD Card. Think of it exactly like the hard drive in your computer.

The final component of interest onboard is the micro-USB port. This is not used for data or connecting to your computer but rather as the power for the Raspberry Pi. The Raspberry Pi used very little power and 5V that USB provides is enough to power it as long as you aren’t using any addition devices plugged into the Pi that use a lot of power.

Here is a quick start guide to help you get started if need to help hooking it up and powering it on.

Loading the Operating System

Every computer needs an operating system (OS). Your Mac runs Mac OS X and your iPhone, iPad, etc run iOS. The OS handles all the interfacing to the hardware so that “apps” can just do what they need to do.

A Raspberry Pi can run many different OSs, but the one you’re going to use here is Raspbian. Raspbian is a version of the Debian Linux distribution dedicated to running on a Raspberry Pi. Therefore it’s perfect for this tutorial!

To get your Raspberry Pi up and running with Raspbian, you’ll first need to download and install it. This is done by downloading something called an “image”. An image is simply a snapshot of a pre-installed copy of Raspbian, ready to copy over onto your memory card to run on your Raspberry Pi.

Downloading the Image

Go to http://www.raspberrypi.org/downloads and look down the page for the Raw Images section. Under the Raspbian sub-section, download the image either as the direct ZIP or using the torrent. The torrent is downloaded using the bit torrent protocol. If you don’t know what that is just download the image directly.

The zip file contains a disk image (a .img file) of the entire installed operating system. Download and extract the image from the zip anywhere you have access to it. Then you are just going to copy the data in the disk image on the SD card (in the next section).

The default root (administrator) username and password are:

Username: pi Password: raspberry

Make a note of these, because they’ll come into play later.